In spring of 2017, Marshall Township resident Patrick O’Brien started having pain in his stomach – the kind that makes a person pop antacids without really suspecting anything serious.

By August of that year, the pain had become excruciating, so he went to the ER, where doctors did scans and a biopsy, revealing stage IV cholangiocarcinoma, a rare and particularly deadly form of cancer that originates in the bile ducts. At the age of 54, O’Brien was given less than a year to live.

As his doctors were formulating a treatment plan, O’Brien got some unexpected good news. A new genetic test revealed his tumor carried the ERBB2 gene amplification, which meant he could take a drug called Herceptin that latches onto the ERBB2 receptor to help his immune system clear away the cancer cells.

“That was the first time I saw the doctors that they were kind of upbeat,” O’Brien said.

He started on Herceptin as well as two other chemotherapy drugs in November. By January, his tumor marker count had plummeted to less than 1% of where it had been at the peak of his illness.

“My oncologist wanted to redo the test because he didn’t believe it,” O’Brien said. “That was the first sign that something pretty dramatic was going on with this treatment.”

He stopped chemotherapy last summer, and his tumor markers are now well within the range of normal.

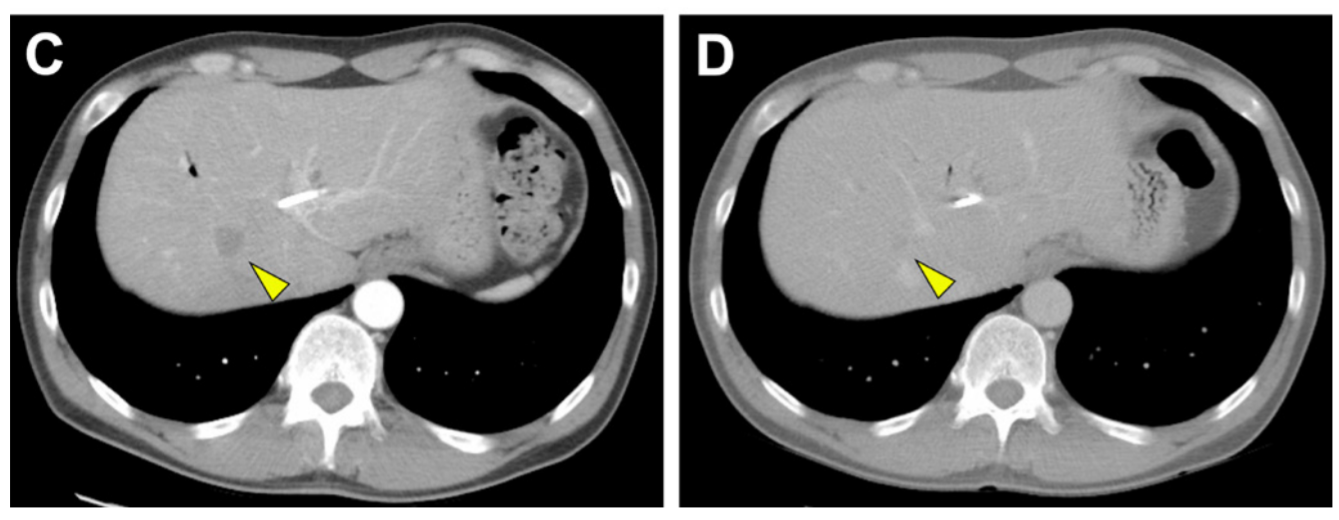

A metastatic lesion on O’Brien’s liver before (left) and 8 months after (right) treatment with Herceptin and chemotherapy.

The genetic test that painted a big, red bull’s-eye on O’Brien’s cancer is called BiliSeq, and it was developed by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center. They published their results this week in the journal Gut. The test is now available for clinical use for patients seen at UPMC and other medical institutions.

So far, the researchers have tested samples from 252 patients with bile duct cancer, and 8% of them had genetic markers, like O’Brien’s ERBB2 amplification, that existing Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs can target directly.

“With BiliSeq, we can detect neoplasms involving the bile duct early and actionable alterations quickly, to decrease the time to appropriate management. This could include surgery or chemotherapy targeted to the specific alteration found in the tumor,” said lead author Dr. Aatur Singhi, assistant professor of pathology at Pitt.

Two of the patients that BiliSeq identified as ERBB2-amplified started Herceptin, and both responded well, Singhi said.

BiliSeq also tackles a particularly challenging aspect of bile duct cancer – it can be really hard to diagnose. That’s because clinically it looks a whole lot like benign narrowing of the bile duct.

“Patients can present fairly early, but one of the frustrating things is that we think we know what they have but we can’t prove it,” said senior author Dr. Adam Slivka, associate chief of clinical services in the UPMC division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition and professor of medicine at Pitt. “When we sample these tumors during endoscopic procedures, the cytologists frequently say, ‘we don’t see a lot of cells in the specimen, but the ones we do see don’t look normal, but we don’t know for sure it’s cancer.’ The medical oncologist won’t give chemo unless everyone is sure.”

Non-cancerous narrowing of the bile duct can be treated with anti-inflammatory medication or an endoscopic procedure, Slivka said, so it would be awful to subject these patients to riskier, more aggressive treatments without confirming that they do, indeed, have cancer.

It’s a problem Slivka has been working on for over two decades.

Earlier he tried inserting various imaging tools into the bile duct to get a better look, but because some patients have such inflamed and narrow bile ducts, it’s a tight squeeze for a scope or probe. Combined with the fact that cancer doesn’t always look the same, there’s a limit to how accurate a visual inspection of the ducts can be.

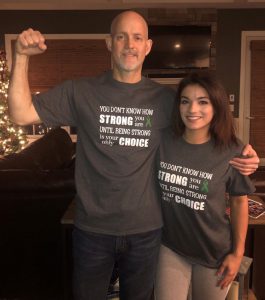

Patrick O’Brien with his daughter, Julie, who hosted a fundraiser for the Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation that raised $1,200.

So, Slivka enlisted Singhi’s help to develop a more definitive test based on genomics.

Singhi had just created a genetic test for early detection of pancreatic cancer, so it stood to reason that they could take a similar tack for diagnosing malignancy in the bile ducts.

And they were right. BiliSeq doubled the accuracy of standard methods. And for some of the most difficult-to-diagnose cases – those involving primary sclerosing cholangitis – BiliSeq increased sensitivity even more.

The hope is to catch the cancer earlier while patients have the most options and the best prognosis. If the cancer hasn’t spread beyond the liver, doctors can either surgically remove the tumor or transplant a healthy liver in its place, which more than doubles the odds of a patient surviving past five years, Singhi said. Right now, fewer than 8% of patients with inoperable bile duct cancer survive beyond five years of their diagnosis.

O’Brien acknowledges his luck. Whereas friends with the same type of cancer went months before getting a diagnosis, he had precise results, down to the molecular level, within a week of being admitted to the ER., and chemotherapy tailored to his tumor’s genetic defects.

“They were doing this research, pushing the boundaries, and I knew nothing about it,” O’Brien said. “I think it’s important that people ask their doctors about that – targeted therapy, genomic testing, immunotherapy, all the new things going on with treatments.”