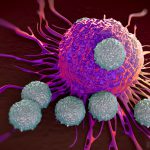

If you think back to high school biology class, you can likely recall learning about T-cells, the mighty white blood cells that live within the body. The powerful cells work tirelessly each and every moment of the day to activate the body’s immune system and fight off pathogens. They’re also the basis of Udai Kammula, MD’s life’s work.

Dr. Kammula, director, Solid Tumor Cell Therapy Program, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, began his career as a surgical oncologist in the 1990s, with a specialization in liver cancer, and completed much of his training at the National Institute of Health (NIH).

“I spent many years training to do advanced surgery, and one of the things that I realized was that once a tumor becomes advanced, surgical tools are limited,” he said.

A lover of his craft and a pioneer in his field, he’s quick to clarify that surgery does remain the most effective method of curing cancer. But without early detection, surgeons are often at a disadvantage, as tumor cells enter the circulation and can migrate throughout the body.

The question of ‘Is there another way?’ lived quietly at the back of Dr. Kammula’s mind as he continued his training, and it came to the forefront as he embarked on a research fellowship with Steven Rosenberg, MD, a pioneer of immunotherapy. Immunotherapy is a treatment strategy that involves using a person’s own immune system to fight cancer. At the time of his fellowship, immunotherapy was considered highly controversial. “It was thought to be this very fringe type of field,” he said.

But while the field may have been critically viewed at the time, Dr. Kammula fondly admits that the fellowship was life-changing for him. “I was bitten by the bug.”

Identifying a Need

Thus began Dr. Kammula’s quest toward his current research. “I think sometimes in life, you fall into something where it feels like the pieces of your personality meld together,” he said. “The obsessive nature in me really loves surgery, but I found I was also getting a different type of thrill from performing an experiment and making a discovery. So I set out to merge those into a career.”

Dr. Kammula spent almost 18 years working at the NIH, where he helped spearhead the field of immunotherapy, developing treatments such as Adoptive Cell Therapy (ACT). During one of his many experiments at the NIH, Dr. Kammula was challenged by an aggressive type of cancer that would not respond to any treatments: uveal melanoma.

Uveal melanoma is a rare and aggressive type of eye cancer that originates in the uveal tract of the eye but has a tendency to viciously spread throughout the body, often to the liver. When metastasis occurs, this cancer is very difficult to treat and the prognosis for patients is grim.

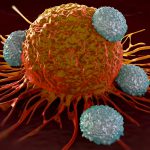

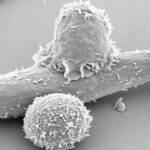

“We had made this quite confusing observation and that the metastatic tumors I was surgically removing from patients with uveal melanoma were chock full of T-cells. And this was a cancer that wasn’t responding to any cell-boosting therapies, so that didn’t make any sense,” he recalled.

Dr. Kammula was determined to make sense of that which did not. He began to wonder what it was about the tumor’s microenvironment that stopped the T-cells from activating and working against the tumor. The question led him toward a major breakthrough: ‘What happens if we cut out the middleman?’

Dr. Kammula and his team decided that they would take the T-cells inhabiting the metastases and grow them externally in the lab by the billions before infusing them back into the patient as treatment. Their plan was met with skepticism and doubt, with Dr. Kammula’s own colleagues arguing the treatment would never work.

“Everyone, including my mentor said it was never going to work — we were never going to see results,” Dr. Kammula said.

“But, we did.”

The Breakthrough

During those initial studies, some of which have been published in Lancet Oncology, Dr. Kammula and his team saw a groundbreaking 35% of patients have either complete or partial regression of their cancer as a result of their treatment. But for every new development made, there was another question to be asked.

“Why does this happen? How do we choose our patients? And of course,” Dr. Kammula said, “how do we make this better?”

He knew he would need the proper resources, team, and space to forge ahead with his research, and discover the answers to his ever-growing list of questions. In 2017, Dr. Kammula received an offer to come to UPMC and lead the cellular immunotherapy program for solid tumors. He instantly knew that it would be the perfect place to further conduct his research, which he calls the tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) trials.

While Dr. Kammula firmly believes there is not a “one-size-fits-all” way to treat cancer, he and his team have created a steady process for their TIL trials.

Once the presence of TILs has been confirmed and extracted from the tumor, the work begins. The treatment begins aggressively but with purpose. Dr. Kammula’s team works to temporarily wipe out the patients’ immune system while the T-cells are multiplied in the lab. Once they have enough T-cells and the patient is ready, they build the immune system back up quickly by infusing the patients with the lab-grown T-cells alongside a boosting hormone.

“It’s like planting seeds,” Dr. Kammula said. “They will blossom, and grow, and multiply and then you can track them circulating the bloodstream.”

One of Dr. Kammula’s patients, Katie Doble, recently shared her success story with WTAE. Katie was only 31 years old and living in Denver when she was first diagnosed with uveal melanoma. The cancer, which began in her eye and had metastasized to her liver and resulted in several tumors, had given Katie a grim prognosis: 6 months to live.

She began intensive treatments immediately, including radiation to her eye. She participated in multiple clinical trials, which she believes bought her more time, before walking through the doors of UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and meeting Dr. Kammula.

Dr. Kammula made her no promises but this: He would do everything in his power to fight her cancer alongside her.

After confirming Katie’s eligibility for the trial and admitting her as a patient, Dr. Kammula’s team took less than a million of her T-cells back to their lab, where they multiplied the cells to reach 111 billion. They then infused them back into Katie and monitored her as the T-cells began to work their magic.

Dr. Kammula and Katie Doble

The T-cells performed exceptionally, and Katie’s cancer responded by regressing. Dr. Kammula surgically resected the last remaining nodule and found that it was still largely composed of the TILs that she had received over a year prior during her treatment trial. She remains under the care of Hillman and receives scans twice a year to check for cancer recurrence and to confirm the T-cells are still circulating, Dr. Kammula said.

More than three years from her treatment, Katie remains cancer-free. “We watch her like a hawk,” Dr. Kammula said, “Thus far, she is doing great.”

Katie told WTAE that she feels “so, so lucky” to have been able to receive treatment at UPMC. “This is incredible care,” she said.

Looking Ahead

Katie’s success story is not an isolated one. Since coming to UPMC and continuing with the TIL trials, Dr. Kammula and his team have been able to replicate his initial results with uveal melanoma, and have also started to extend the treatment with other hard-to-treat cancers, such as pancreatic cancer.

Dr. Kammula believes that his work is just beginning, and his insatiable desire to answer the questions that arise throughout the trials have him more focused on the future than ever before. He and his team will continue to conduct their trials to gather data and curate treatment plans, while also keeping an eye on the horizon.

Their most recent publication, in Nature Communications, explains one of the team’s more recent endeavors: the development of a new clinical tool that predicts which patients will respond to adaptive therapy. The work, supported by UPMC Enterprises, is helping improve personalized therapies and avoid futile treatments for metastatic uveal melanoma.

The team also intends to continue expanding the treatment to other forms of cancer as their work continues, and as time goes on, they are beginning to examine if the treatment will eventually require “boosters” to keep cancers at bay.

“Cancers are tricky,” he said, “They are the ultimate at mutating, changing, and evolving.”

Dr. Kammula and his team will continue to monitor their patients as the years go by, but they remain confident and inspired by the promising results they’ve achieved thus far.

Their method really boils down to the fact that the treatment comes from the patients themselves. With no small amount of help from Dr. Kammula and his team, the T-cells work as they were intended to and conquer the patient’s cancer.

“We give patients what nature might not have,” Dr. Kammula phrased the phenomenon.