Ricardo Iriart smiles when he talks about his wife, Ángeles. They met in college, and he was immediately drawn to her striking beauty.

“It took me a couple of weeks to befriend one of her friends first, and we finally got introduced,” he says. “I loved her great heart, her smarts, her sense of humor, the fact that she was a natural leader with lots of friends and always the center of any party.”

She was also a natural athlete, the star player on their school’s field hockey team. “She was good at whatever she tried, golf, tennis, you name it,” Ricardo says.

The young couple eventually moved from Argentina to the United States, where they raised three children.

In 2021, finally empty nesters, Ricardo and Ángeles were looking forward to retirement and making plans for the future. Ángeles, still active into her 60s, was playing tennis with a friend when she suddenly felt a terrible headache. Ever the competitor, she rested for a few minutes, shook it off, and returned to play. Soon, she collapsed and was rushed to the emergency room.

Ricardo said his wife suffered a spontaneous hemorrhage as a result of a congenital condition called an arteriovenous malformation, or AVM, essentially a tangle of blood vessels in the brain. Doctors told Ricardo that the accident had left Ángeles with no cognitive function, but he said he never truly believed them.

“I always knew she was aware in some way,” he said. “She is my wife. I know her. I could see in her eyes if something was bothering her. I would hold her hand and talk to her until she was at peace.”

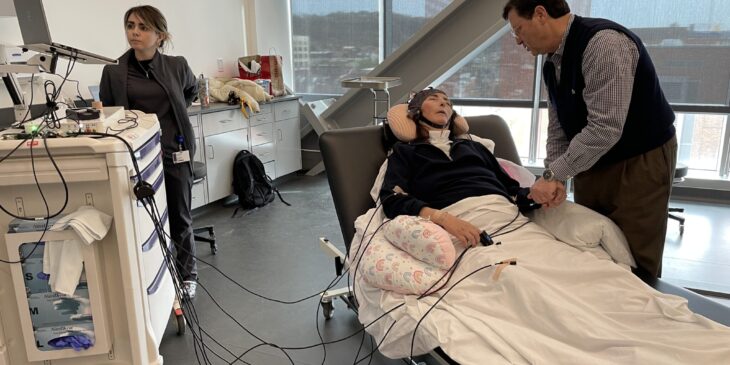

Ricardo’s belief in his wife’s consciousness was validated when she recently participated in a clinical trial investigating the use of a wearable brain-computer interface (BCI) to help patients like her communicate.

“We have had an understanding over the last several years that we’re not accurately picking up the degree to which people can perceive their environment and understand their situation,” said Amy Wagner, M.D., professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Pittsburgh and co-principal investigator on the study. “The goal is to empower these patients to become active participants in their care and recovery.”

Wagner specializes in treating patients with brain injuries so severe they are no longer able to interact with others in a way that demonstrates consciousness. Research using EEG and functional MRI suggests that a traditional clinical exam may be insufficient for detecting an individual’s level of consciousness.

Wagner connected with Katharine Hill, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, director of Pitt’s AAC & BCI iNNOVATION Lab, who investigates ways to use brain-computer interface devices to help individuals like Ángeles interact with the world.

“People with significant neurologic disorders, like ALS, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease or locked-in syndrome all have a need for an alternative way to communicate,” said Hill, co-principal investigator of the study.

The team used a wearable EEG-based BCI system developed by a medical engineering company in Austria. This system uses a flexible cap fitted with 16 electrodes to record brain activity non-invasively. While the BCI industry continues to grow, these systems are not yet routinely used in clinical care.

“Each individual with a disorder of consciousness (DoC) presents uniquely. If you’ve met one person with a disorder of consciousness, you’ve met one person with a disorder of consciousness,” said Amber Lieto, M.S., CCC-SLP, a speech-language pathologist and graduate student researcher on the project. “Everyone is different, and we’re only just beginning to understand how clinicians can use this technology to assess cognition and support communication.”

The team customized protocols for each participant based on the detectability of specific brain signals, the effectiveness of different sensory cues and the quality of the recorded signal. For instance, Ángeles was asked to think the words “sí” or “no” whenever she felt vibrations delivered by a vibrating rod placed on her body. Another participant, Joshua Robinson, imagined throwing a ball with either his right or left arm. Meanwhile, Gabe Brown responded to yes-or-no questions about his personal life, such as the color of his house, his wife’s name, and his favorite basketball team.

“Gabe is a Celtics fan,” said Dr. Siulam Koo, D.O., a fellow physician with the Brain Injury Medicine program at Pitt. “We were able to get a sense of what he likes about them, who his favorite player is, what he thinks of their chances in the playoffs.”

The team presented their research at the International BCI Society Meeting in June, sharing both Gabe’s and Ángeles’ stories. The study, funded by the Beckwith Institute and the UPMC Rehabilitation Institute, represents an important step forward in understanding the clinical applications for brain-computer interfaces.

“We’re very grateful for their support in taking a chance on us with this out-of-the-box technology,” said Wagner. “We think the data we’ve been able to collect will provide a valuable starting point for other funding sources to further advance this research.”