Earlier this month, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration ordered manufacturers to stop selling mesh for the transvaginal surgical approach to repair pelvic organ prolapse – a condition in which the bladder, uterus or rectum fall out of place – due to insufficient evidence that these particular meshes are both more effective and at least as safe as native tissue repair.

Dr. Pamela Moalli, professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and pelvic reconstructive surgeon at UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital, views the mandate as premature. She points out that transvaginal mesh fills a real need for many women, and that the product should be improved rather than abandoned. Moalli just received a five-year, $2.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to make better mesh.

About 33% of women experience pelvic organ prolapse at some point in their lives, usually due to childbirth or aging. When the pelvic organs bulge into the vagina – or in some cases even protrude outside the body – it can lead to pain, incontinence and shame.

For those who choose surgical correction, there are three options, Moalli said.

First, a woman could choose to have the surgeon perform the repair using only her own tissues. A major drawback is that the procedure typically requires a hysterectomy. Also, large multicenter randomized trials showed that 30% to 40% of these surgeries fail within two years, and 60% by seven years, mainly because the pelvic tissues tend to be weak in women with prolapse.

The second option for surgical repair is to insert a piece of mesh through an incision in the abdomen, a procedure called a sacrocolpopexy. This type of mesh was not part of the FDA’s order. The success rate is high and the complication rate is low. The drawbacks are that sacrocolpopexies are difficult to perform, so not all hospitals can offer them, and not all patients can tolerate them, especially those who have had significant abdominal surgery in the past.

The third possibility is to insert mesh through an incision in the vagina. This is the approach the FDA is worried about, Moalli said. Transvaginal mesh surgeries tend to have a higher complication rate and a lower success rate than meshes implanted abdominally, but according to Moalli, there are still situations where it’s useful.

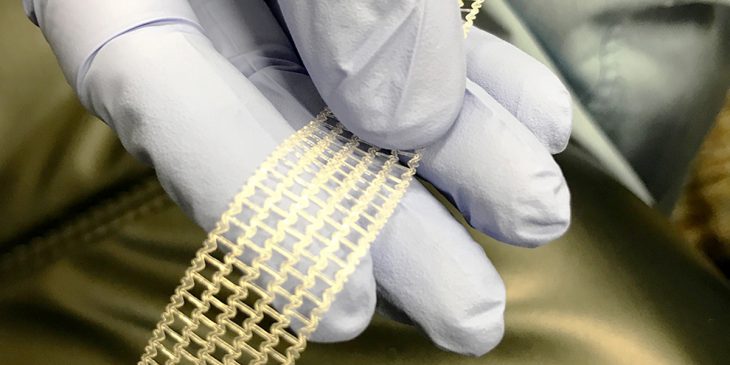

The real problem, Moalli said, is that prolapse meshes – originally intended to repair hernias – were never designed to be used this way. Most meshes are made of polypropylene, which is a very stiff polymer. To mitigate its stiffness, manufacturers extrude polypropylene into thin fibers and then knit them into a mesh.

But most knit patterns permanently deform and wrinkle under the kind of stresses needed to suspend the vagina, and that’s what can lead to complications, Moalli said.

Since polypropylene meshes are still much stiffer than the vagina, that leads to another problem called “stress shielding.” All tissues in the body, including the pelvic organs, need to experience forces to maintain their structure and function. When shielded by an overlying mesh, the vagina thins and withers.

Moalli has partnered with Dr. Steven Abramowitch, associate professor of bioengineering in Pitt’s Swanson School of Engineering, for over 10 years to provide insight into problems with current meshes and to design a better material.

Moalli has partnered with Dr. Steven Abramowitch, associate professor of bioengineering in Pitt’s Swanson School of Engineering, for over 10 years to provide insight into problems with current meshes and to design a better material.

“Our group will evaluate the use of elastomeric polymers whose inherent stiffness is similar to that of the vagina but are also tough enough to meet the physiologic loading demands within the pelvis,” Abramowitch said. “The materials we chose can be 3D printed, which allows us to adjust the geometric features of the device and design it so that we reduce issues of the current meshes, such as wrinkling and permanent deformation.”

Abramowitch and Moalli hope that their prolapse mesh, designed specifically with the vagina in mind, will significantly improve the success rate of pelvic organ prolapse surgeries while minimizing complications.

“Issues that negatively impact the quality of life and are specific to women often do not get the attention that they deserve in research,” Moalli said. “This is an opportunity to develop solutions for women that are designed based on an understanding of the uniqueness of female anatomy and biology.”