For centuries, people thought that blindness was incurable – once the darkness sets in, it never retreats. Unlike in fish and frogs, the human retina doesn’t regenerate, and the vision loss caused by damage to cells in the back of the eye – be it genetic or physical – can rarely be fixed. But new research suggests that regrowing the retina may not be science fiction after all.

Dr. Jeff Gross

In a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last month, scientists at Pitt’s Department of Ophthalmology found that immune cells in the eyes of a zebrafish are indispensable for the regeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium, or RPE – a thin layer of flat, darkly colored cells that maintain the health of the light-sensing cells of the retina. In the future, the researchers hope to harness that feature to regenerate the RPE and restore sight in humans.

“We are finally beginning to understand the mechanism of retina and RPE regeneration,” said senior author Jeff Gross, professor of ophthalmology and developmental biology at Pitt. “Even though there is a lot of work yet to be done, we are standing at the frontier of biology.”

It might come as a surprise to many, but the retina of zebrafish – those tiny blue-striped creatures so common in fish tanks in our homes, offices and classrooms – is uncannily similar to the human retina, both in structure and in function.

Just like the human eye, the eye of a zebrafish is lined with RPE cells that serve many important functions, providing nutrients to the retina and maintaining the integrity, structure and function of cones and rods – the light-sensing cells that allow perception of colors and shades of gray.

Dr. Lyndsay Leach

In fact, RPE cells are so important that their damage causes injury to the light-sensing cells in turn. “Simply put, RPE cells are fascinating,” said lead author Lyndsay Leach, a research scientist at Pitt.

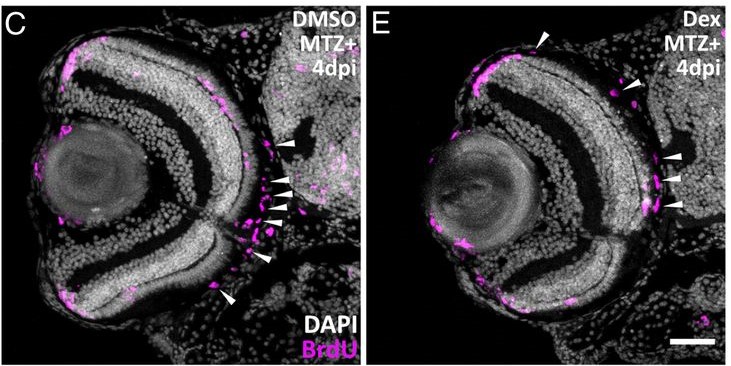

The scientists discovered that the immune system is intimately intertwined with the process of RPE regeneration in zebrafish. Using various genetic and imaging techniques, the researchers noticed that regeneration requires the activation of different immune cells, and that manipulating the immune pathway can determine if the regenerative process will succeed or fail.

The researchers hope to use that new knowledge to explore the possibility of reawakening the intrinsic but long-hibernating capacity of the human RPE cells to regenerate.

“We hope to leverage what we learned about RPE regeneration in zebrafish and use that information to develop new therapies in the human eye,” said Gross.

Perhaps, one day, the long-lost secrets of evolution can be used to cure human blindness.