When the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health dean arrived at her appointment to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, she expected it to be an important occasion.

But she was surprised to realize how uniting it would be. That’s because Dr. Maureen Lichtveld moved to Pittsburgh and took the helm of Pitt Public Health this winter in the midst of the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic – meaning she hasn’t met in person with the vast majority of the school’s faculty, staff and students.

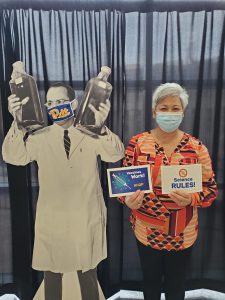

Dr. Lichtveld poses with Dr. Jonas Salk after receiving her COVID-19 vaccine. Salk developed the polio vaccine 66 years ago this week.

At the Petersen Events Center vaccination clinic last week, she personally greeted several student and staff volunteers – and looks forward to meeting many more as vaccination becomes widespread.

“I can’t wait to see everyone in person – students, faculty and staff – and be able to engage,” Lichtveld said. “Public health, in particular, is about people. This pandemic is keeping us from where we’re supposed to be and should be – in our communities where our science is translated to helping people.”

Lichtveld said she had a mild reaction to the vaccine – some nausea and a headache – but nothing that disrupted her plans or kept her from work or exercise.

“Fortunately, in our country – and that’s not necessarily true globally – we make a significant effort to be sure the vaccines are safe,” she said. “There is not a vaccine or medication without some risk of side effects, but the vaccines are safe and each individual’s risk from COVID-19 is far greater than that posed by the vaccines.”

And when an individual refuses to be vaccinated, the risk they assume is shared with their community because the virus can keep spreading.

“When you do not vaccinate, you not only put yourself at risk, you put your family at risk, you put your Pitt family at risk, you put the community at risk and you actually prevent all of us from going forward,” she said. “All of us want to go out to dinner, go to a football or hockey game, attend a show at the theater. The more people who are hesitant to be vaccinated, the longer it will take us to go back and enjoy what we do.”

As she left the clinic, Lichtveld shared a (masked) smile with another important Pitt public health figure – at least in spirit – snapping a photo, with the assistance of Pitt Public Health staff volunteer Kelly Tatone, next to a life-sized image of Dr. Jonas Salk. Sixty-six years ago this week, he developed the polio vaccine next door to the Pete at the Pittsburgh Municipal Hospital, which is now known as Salk Hall.

“I held up two signs, one that says, ‘Vaccines work!’ and I’m hear to tell you, I’m fine, I’m working,” said Lichtveld, who holds the Jonas Salk Chair in Population Health. “And the other one says, ‘Science RULES!’ and the message here is: It took a cross-disciplinary, interprofessional strategy to be vaccinated and Pitt is emulating that.”