Persistent coughing, frequent lung infections, fatigue – these are some of the most common symptoms of cystic fibrosis, a devastating genetic disorder without a cure that affects more than 70,000 people worldwide.

But along with classic symptoms of cystic fibrosis, a small subset of patients also develop liver disease, which causes liver inflammation and scarring due to perturbations in bile flow, and can lead to cirrhosis and liver failure. Doctors don’t know why some patients develop liver disease and some don’t, but the mechanism of liver disease development in patients with cystic fibrosis became clearer thanks to a new paper published by University of Pittsburgh scientists in the journal eLife.

The researchers discovered in mice and humans with cystic fibrosis, that cells called cholangiocytes – which line bile ducts that crisscross the liver tissue and serve as pipelines that shunt toxic byproducts of body metabolism – lack a critical interaction between proteins that control cell regeneration and inflammation. Without that interaction, cholangiocytes become inflamed and fibrotic – offering an explanation as to why cystic fibrosis pathology in the liver manifests the way it does.

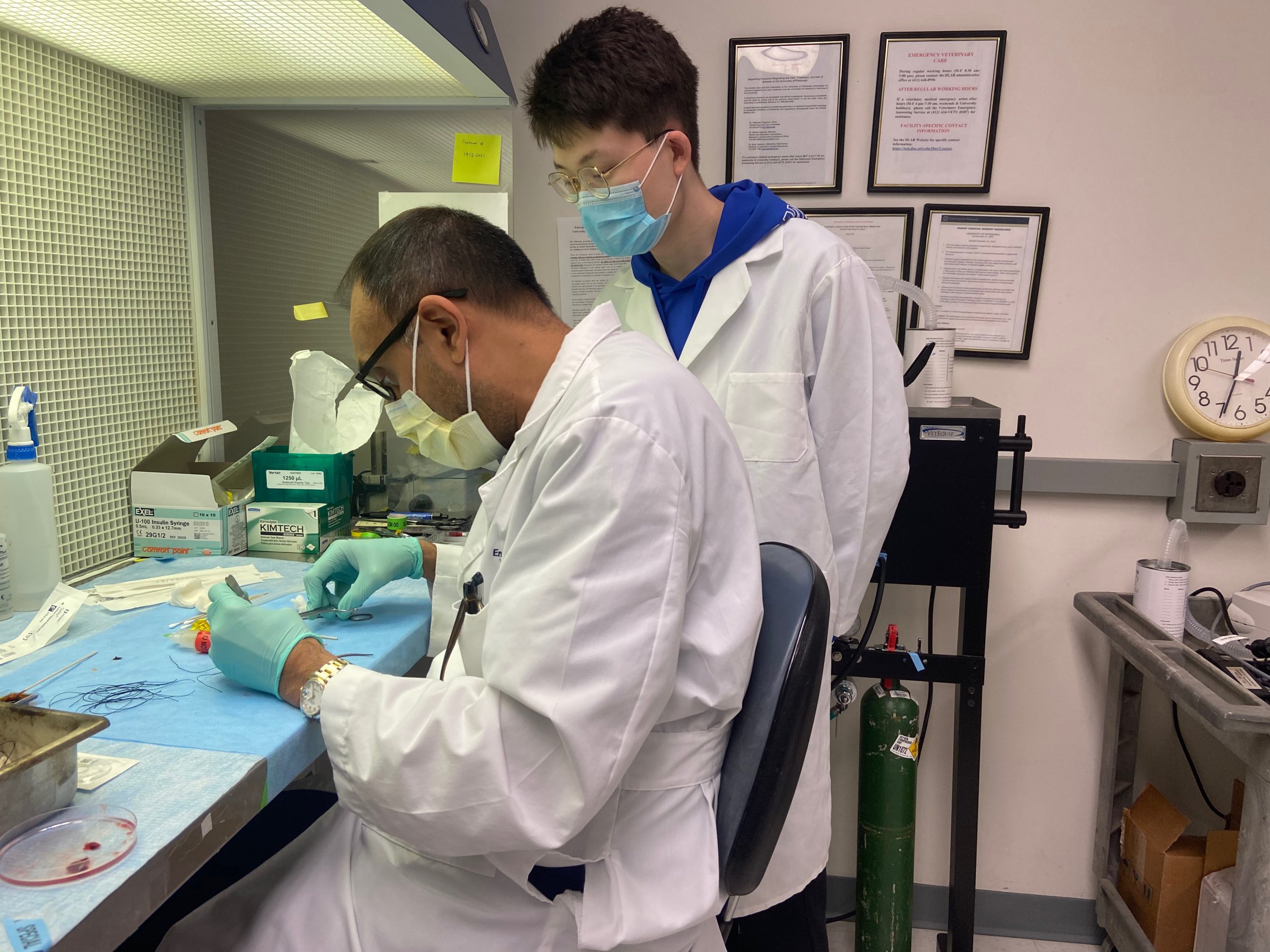

Dr. Satdarshan Monga (left) working in the lab with trainee Shikai Hu (right)

“This missing interaction is at the core of the pro-inflammatory environment in the fibrotic liver – it adds insult to injury and makes the disease worse,” said senior author Satdarshan (Paul) Monga, M.D., professor at Pitt’s Department of Medicine. “This discovery sheds light on how bile duct cells that are not malignant by nature can suddenly turn against the body.”

Cystic fibrosis – a genetic disorder diagnosed in about a thousand new patients in the United States each year – starts with one faulty gene. Hundreds of mutations in the genetic code for a protein called CFTR, or cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, can render this molecule inactive, leading to a buildup of thick mucus in the lungs and symptoms in other parts of the body.

Building on experiments in mice, Pitt researchers realized that the inability of the mutated CFTR to regulate cellular location of two proteins controlling inflammation and cell repair might have something to do with clogged bile ducts in cystic fibrosis patients.

The group discovered that under normal circumstances, CFTR acts as a molecular anchor, tightly tethering itself and the two other proteins together, preventing them from spontaneous activation. But when CFTR is gone, or when its ability to link up to its partners is disrupted because of mutations, the other two proteins become active and cause overgrowth of bile duct lining and progressive inflammation.

Sungjin Ko, D.V.M., Ph.D.

The discovery wasn’t an instant “aha moment,” though.

“For me, this is the joy of science. No one can tell you where to look for answers – you have to look hard to find them – but when things fall into place, it’s the most gratifying feeling,” said first author Shikai Hu, a visiting scholar at Pitt and a member of the first cohort of M.D.-Ph.D. students in the joint program between Pitt and Tsinghua University in China. “Doing an experiment and confirming for the first time that what we saw in mice was also what we see in patients with cystic fibrosis was very exciting and validating.” The researchers emphasize that there are still many questions that are left unanswered – but they are optimistic that one day, the full picture of molecular changes caused by cystic fibrosis in the liver will reveal itself.

“Observing changes in tissue morphology can only take us so far,” said co-corresponding author Sungjin Ko, D.V.M., Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Pathology. “It takes a lot of effort to correlate visually observed changes to their molecular signatures, but understanding these intricacies is key to developing better therapies.”