For decades, the field of Alzheimer’s disease research was plagued by a dilemma: Scientists and clinicians knew that accumulation of tau protein – tangles of jumbled protein fibers clogging the brain’s nerve cells – is an important marker of disease severity. But the researchers still had to wrestle with the technical limitations of detecting small amounts of tau proteins; some tools that help identify tau tangles are more sensitive than others and can flag early Alzheimer’s disease while another tool might erroneously show that the patient is Alzheimer’s-free.

These limitations create problems for researchers who want to compare their results. If the two groups didn’t use the same tau detection tools, it’s hard to accurately compare the findings between the studies.

Tharick Pascoal

To put an end to this discrepancy, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh were recently awarded over $40 million distributed over five years. The National Institutes of Health grant was given to Department of Psychiatry Assistant Professor Tharick Pascoal, M.D., Ph.D.

“The problem of comparing tau tracers is very acute,” said Pascoal. “It’s often difficult to compare data about Alzheimer’s severity and to make conclusions that are benefitting patients the most. I’m excited to help unify the standards of Alzheimer’s disease diagnostics and move the field forward.”

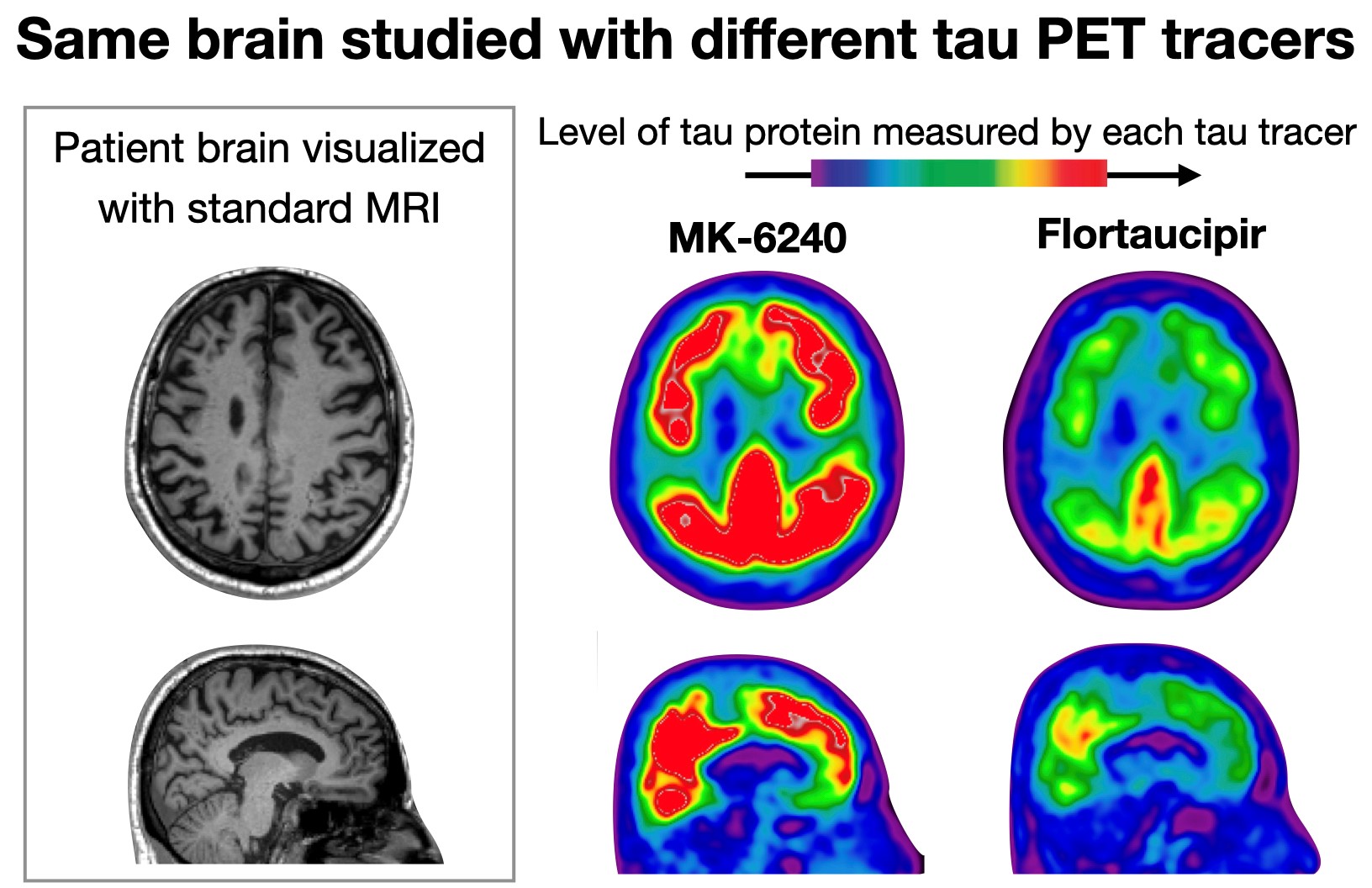

To directly measure the amount of tau protein and detect its location in the brain, researchers use slightly radioactive compounds called “tau tracers,” which bind to tau in the brain and make it visible on a PET scanner. But the tracers aren’t perfect.

One frequently used tracer – called [18F]Flortaucipir – can detect miniscule amounts of tau in the brain, but can also sometimes erroneously indicate the presence of tau where there isn’t any. Another tau tracer, [18F]MK-6240, is even more sensitive to tau but can also erroneously indicate the presence of tau in brain regions different from areas that light up with [18F]Flortaucipir – which creates additional difficulties when comparing brain scans acquired using different tools.

Same brain studied with different tau PET tracers

By comparing these tracers head-to-head, the researchers are hoping to get a clear picture of the differences and similarities between the two, and describe once and for all which tracer is more appropriate to use in patients with sub-clinical Alzheimer’s disease and which for patients with symptomatic Alzheimer’s. Their ultimate goal is to build a scale that could be used to harmonize scans obtained with the different tracers and help researchers and clinicians make more informed treatment decisions.

The scientists aim to enroll 620 people – those with and without cognitive impairments, and patients with Alzheimer’s-associated dementia – and follow them for 18 months, looking at brain scans acquired with both tracers and testing patients for other visual and biological markers of Alzheimer’s disease.

The study is expected to involve eight medical centers across the United States and Canada, including Pitt, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, Washington University in St. Louis, Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Houston Methodist Neurological Institute and Brown University in Providence, as well as McGill University in Canada.

“The biggest heroes of this work are the patients themselves,” said Pascoal. “This study wouldn’t be possible without sacrifice and commitment of so many people who are contributing their time to research.”

Suzanne Baker, of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, is a co-principal investigator on this project.