To date, over 170,000 people in the United States have died from COVID-19. In addition to deaths from the virus, 150,000 more “deaths of despair,” caused by suicide and drug or alcohol overdose, could occur over the next 10 years due to the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic. This prediction highlights the urgent need to expand access to care for conditions other than COVID-19, including substance use disorders (SUDs).

Coleman Drake, Ph.D.

SUD treatment typically occurred face-to-face before the pandemic, with regulatory barriers often restricting tele-SUD, the remote delivery of SUD-related health care services. Reimbursement was limited; regulatory requirements ensured controlled substances were predominantly prescribed in person, and licensing requirements prohibited providers from treating patients in other states via telehealth.

With COVID-19 came extensive changes to tele-SUD policy, allowing providers to initiate buprenorphine treatment virtually and relaxing reimbursement and provider restrictions. Tele-SUD visits have grown exponentially, with group therapy sessions hosted virtually, contactless medication pickup and patient-provider communication occurring over phone calls and texts.

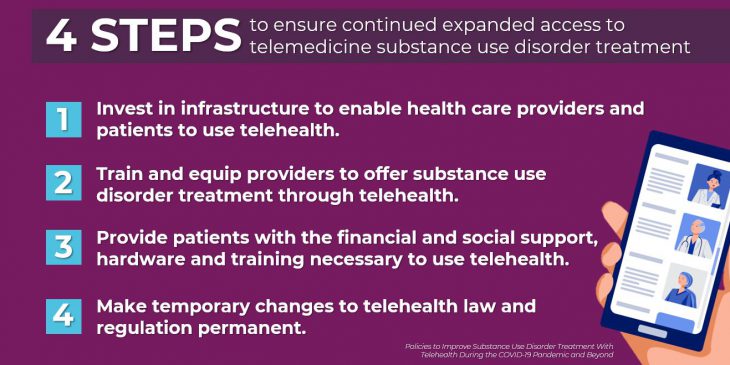

The four critical steps outlined below can ensure this transition to tele-SUD is a long-term solution for improving the health of people with substance use disorders, particularly opioid use disorder:

1. Invest in infrastructure to enable health care providers and patients to use telehealth.

My prior research found that over 40% of the most rural counties in the United States lack the broadband infrastructure necessary for video-based telehealth visits. The implementation of 5G cellular networks will increase the range and quality of wireless connections, helping quarantined patients with SUDs stay engaged in treatment. Smart 5G investments will help to support patients with SUDs and other chronic conditions long after the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Train and equip providers to offer SUD treatment through telehealth.

In addition to internet access, funding is needed to train and equip providers to administer SUD treatment through telehealth. A hub-and-spoke model, with trained local providers facilitating SUD treatment for patients with support from a specialized hub, could help to ensure that those with SUDs start and continue treatment during the pandemic and beyond. This setup could also address many of the mental health and substance use crises that occur alongside epidemics by connecting patients to specialists in both rural and urban areas.

3. Provide patients with the financial and social support, hardware and training necessary to use telehealth.

These efforts depend on successfully enabling patients to use telehealth. An inability to pay for internet and cellular data plans, limited digital literacy and restricted access to technology present major barriers for SUD patients, who often experience financial hardships and housing instability. CARES Act funding could provide patients with tablets and the financial support and training necessary to use them for tele-SUD. In the meantime, providers should continue using telephone-based services, which require less training, technology and funding.

4. Make temporary changes to telehealth law and regulation permanent.

In response to the pandemic, many states have eliminated restrictions on the types of providers who can deliver tele-SUD, suspended in-state licensing requirements for telehealth delivery and mandated Medicaid reimbursement for telehealth services. These changes should be made permanent to create stronger financial incentives to provide long-term tele-SUD services.

Although the health and economic consequences of COVID-19 are staggering, the pandemic has enabled potential improvements in the treatment of SUDs and other chronic conditions with telehealth. If the medical profession succeeds in using this trying time to learn about and invest in telehealth, it could lead to a transformed, flexible SUD treatment system that is a vast improvement over that which existed before the pandemic.

Dr. Drake is an assistant professor of health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health. Visit the Journal of Addiction Medicine website to download his full commentary.