Air pollution can have dangerous health consequences, especially for children with asthma. New research from UPMC and the University of Pittsburgh has found that the Air Quality Index (AQI), a measure of overall air quality, was linked with asthma-related hospital visits among children in Allegheny County.

Dr. Franziska Rosser

The study, published recently in Annals of the American Thoracic Society, indicates that even moderate AQI, which is considered safe for most people, could send some kids to the hospital. The findings, which are the first to link U.S. AQI to childhood asthma outcomes, are a step toward helping clinicians use the AQI to make recommendations for their pediatric patients to reduce the health impacts of air pollution.

“Children are particularly sensitive to air pollution because their lungs are still developing. For patients with asthma, high levels of air pollutants can worsen symptoms and trigger asthma attacks,” said lead author Dr. Franziska Rosser, pediatric pulmonologist at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and assistant professor of pediatrics at Pitt. “Current guidelines for people with asthma recommend avoiding outdoor activities on days when air pollution is high, but we need more evidence-based data on which levels and metrics of air pollution should inform these decisions.”

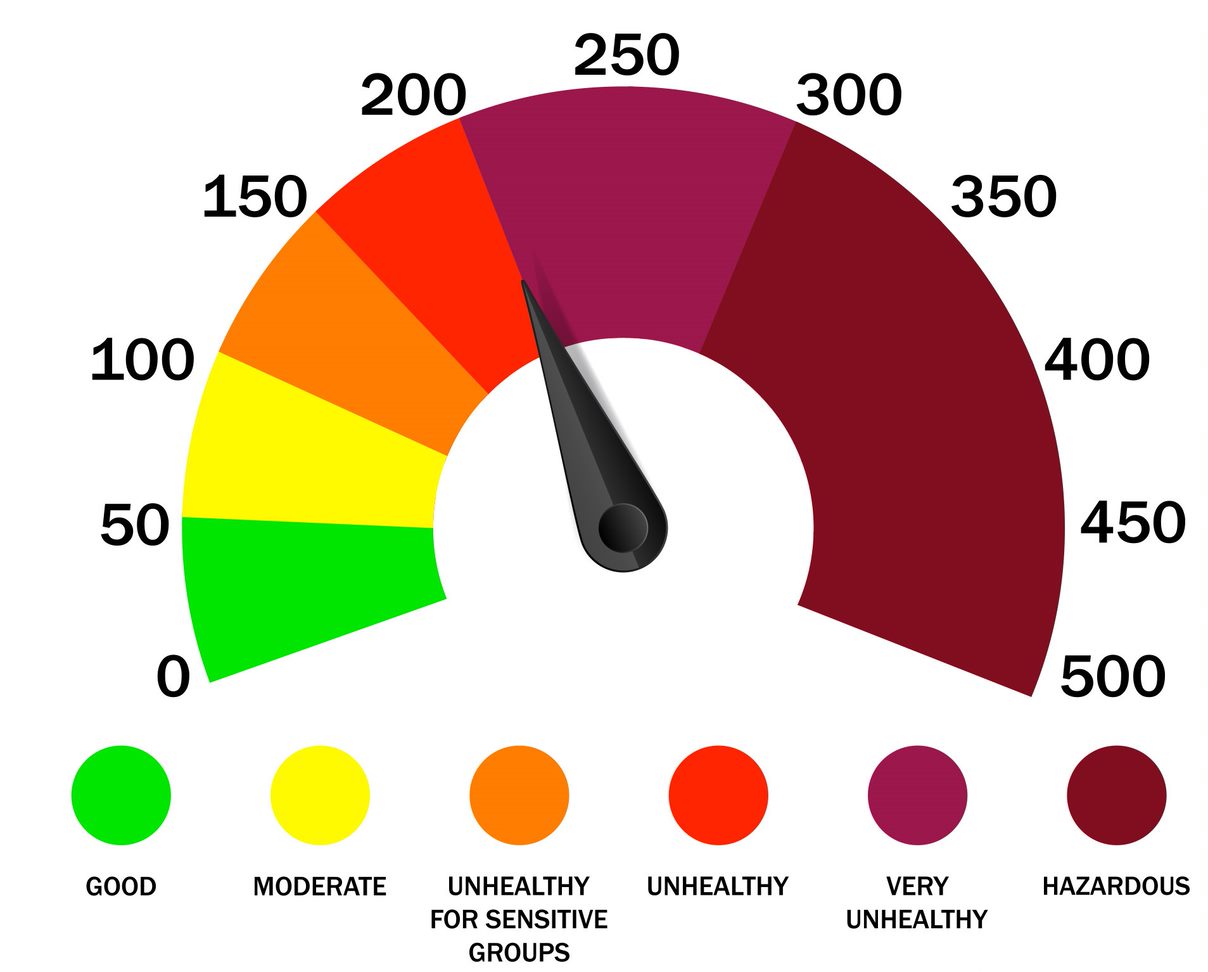

Currently, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program suggests using AQI, a real-time air quality index that is freely available on the AirNow website and mobile app. An AQI below 50 is classified as good and of little to no risk, whereas values between 101 and 500 are considered increasingly unhealthy. AQI values between 51 and 100 are considered moderate, and risky only for those who are “unusually sensitive,” but Rosser says it is difficult for clinicians to know who belongs to this group.

To learn more about the link between AQI and asthma, Rosser and her team examined records from UPMC Children’s Hospital between 2010 and 2018. They found that the higher the AQI, the higher the odds that kids would end up in the emergency department and hospital due to asthma, even on days with moderate AQI values.

“Pittsburgh notoriously ranks among the worst cities in the U.S. for pollutants that drive AQI values, especially fine particle pollution,” said Rosser. “Almost half the year may be spent in the moderate range.”

This slightly elevated but sustained AQI presents a challenge for clinicians making behavioral recommendations to patients.

“In the western U.S., for example, you see AQI spikes of 200 to 300 during wildfires. In these areas, it makes sense to advise everyone to stay indoors and limit their exposure, maybe a few days or weeks out of the year,” explained Rosser. “But when we talk about Pittsburgh, and about kids sensitive to values in the moderate range, it is an enormous burden to ask them to modify their behavior for almost half the year. Going outside to play and exercise is such an important part of an overall healthy lifestyle.”

The association between air quality and asthma-related hospitalizations was strongest among children aged 6 through 11 and Black children.

According to Rosser, younger children may be at greater risk from air pollutants because they have high respiratory rates, often spend a lot of time outside and tend to breathe through the mouth, which may not be as good as the nose at filtering out pollutants.

However, the reasons behind elevated risk for Black children are more complicated.

“Black children are diagnosed with asthma and experience asthma-related emergency visits and hospitalizations at higher rates than their peers. This is a health inequity that doesn’t have to exist: It is based on social structures, including racism,” said Rosser. “And this disparity is worsened by the distribution of air pollution in the U.S., which disproportionately burdens persons of color.”

Rosser worries that recommendations to limit outdoor activity when Allegheny County’s air quality is in the moderate range are unfair to vulnerable kids and could reinforce existing inequities in the health system.

“It is really unfair to make any individual person responsible for mitigating the effects of air pollution, which is a societal and global problem. The best intervention is to work toward clean air, and we need cleaner air in Allegheny County.”

Rosser recommends parents use the AQI to help learn if their child’s asthma is triggered by outdoor air pollution. If parents notice their child’s asthma is worse a day or two after playing outside in the AQI yellow zone, she advises parents to talk to their child’s health care provider about ways to keep their child active outside and asthma well-controlled.

Christine Khoury is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine’s Center for Neuroscience. She is participating in the UPMC Science Writing Mentorship Program.