When Dr. Tiffany Gary-Webb helped develop the “Health Equity Now” theme of this year’s American Public Health Association annual meeting, she realized that the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health had something special to contribute.

Dr. Gary-Webb, who last year became Pitt Public Health’s first female African American tenured faculty, organized a session at the annual gathering of tens of thousands of public health professionals in San Diego to share the breadth of groundbreaking research and partnerships the school has formed in the past several years. Titled “Health Equity for African American Populations across the Lifespan,” the session drew a standing room only crowd.

Dr. Noble Maseru, director of Pitt Public Health’s Center for Health Equity and associate dean for diversity and inclusion, kicked off the session by making sure everyone was on the same page.

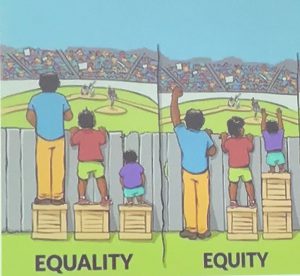

“Equality is not the same as equity,” he said, showing an illustration of three people of different heights trying to see over a fence. Equality would be giving them all the same sized box to boost their height – the tall man can now see over the fence, but the short child still can’t. Equity is when everyone is given the boost they need so that they are all at an equal height to see.

At its simplest, the illustration is a metaphor designed to explain how people who are born into wealth and education, and who are white in a society that still struggles with racism, need less of a boost than people who do not have those privileges, in order to achieve the same goals.

Infant Mortality

Dr. Dara Mendez, assistant professor of epidemiology at Pitt Public Health, explained how health inequities can begin before a child even takes her first breath.

“In the U.S., black women are two times as likely to have their infant die,” she said. “In our county, it’s three times.”

She showcased two projects in Allegheny County that seek to improve infant mortality rates:

The Infant Mortality Collaborative, a program of the Allegheny County Health Department that brings together dozens of organizations with the overall mission of giving “every baby born in Allegheny County a chance to celebrate their first birthday.” So far the collaborative has issued an evidence-based report that explores the problems, and a variety of stakeholders are working together toward change.

The Pittsburgh Black Breastfeeding Research Study, which is a collaboration between the Pittsburgh Black Breastfeeding Circle and Pitt to examine factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and duration among black women in Pittsburgh. Initial results indicate that there are high rates of black women who start breastfeeding but then face challenges continuing to breastfeed through their child’s first year of life, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Youth Violence

In Allegheny County, one of the leading causes of death for black adolescents and young adults is violence, Richard Garland, M.S.W., assistant professor of behavioral and community health sciences at Pitt Public Health, said, picking up where Mendez left off.

“We look at violence as a disease,” he said, explaining the community projects his group administers and how they approach violence through that lens.

The Life Coaches program works on prevention by sending certified coaches into the community to form relationships with at-risk youth and connect them to services.

The Gunshot Reoccurring Injury Prevention Services (GRIPS) program seeks to interrupt the “infection” cycle and provide treatment by going into the hospitals every time someone is shot and offering them and their contacts case management and social support.

The Homicide Review is an annual report that examines every homicide in Allegheny County and makes the analysis freely available with the aim of changing community norms by encouraging conversation about these deaths and the neighborhoods where they occur.

Chronic Diseases

Gary-Webb, who is also chair-elect of APHA’s Epidemiology Section, concluded the health equity lifecycle by sharing Allegheny County’s efforts to tackle chronic diseases.

“We have a huge racial disparity between African Americans and whites when it comes to diabetes and cardiovascular disease,” she said.

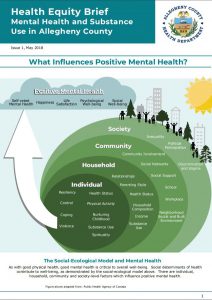

Approximately every five years, the county does surveys to get a pulse on the health of its residents and then develops a “Plan for a Healthier Allegheny” that tackles five priority health areas: access to care, chronic disease prevention, mental health and substance use, maternal/child health and the environment.

Gary-Webb and her team created “Health Equity Briefs” that turn the plan’s dry language and charts into short, engaging reports full of colorful infographics that lay out the issues. Each brief ends with an explanation of what Allegheny County is doing to close the gap.

“We aimed to make these accessible to the general public so that they can give feedback and, if they’d like, participate,” she said.

Finally, Gary-Webb shared a project Pitt Public Health did with the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank to analyze its effort to bring an affordable mobile market, called the Green Grocer, to communities that don’t have ready access to fresh, healthy food.

The analysis found that the mobile food bank was associated with a 13 percent increase in consumption of vegetables in Homewood and a 20 percent increase in Clairton. The team is now collecting data to guide the Green Grocer’s nutrition and marketing efforts.

Following the session, the presenters were swarmed with questions from the audience, many asking how they can emulate the work toward creating health equity in Pittsburgh.

“Pitt Public Health is unique in that we are one of the few schools to have such a concentration on health disparities and equity,” Gary-Webb said. “So our goal with this session was to share how we’re all doing this great research, but also highlight how we’re connecting with our community. I hope it inspires our colleagues in other cities.”