Some people who receive treatment for binge eating find themselves relapsing, while others don’t. This reduced long-term success in treatment prompted Dr. Britny Hildebrandt, a licensed clinical psychologist and researcher specializing in binge eating disorders, to look at the underlying brain processes in a new study.

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine recently published a study in the journal Appetite that found potential neural mechanisms underlying chronic binge eating in mice. These results yield new insights and will inform the development of treatment options for binge-related eating disorders.

Binge eating is a behavior classified as a loss of control around eating in a discrete amount of time, such as within two hours. During a binge eating episode, individuals often eat food that is highly palatable — sweet and high in fat, but low in nutritional value. Although commonly assumed to only occur in binge eating disorder, binge eating behaviors can be found in other eating disorder diagnoses, such as anorexia nervosa binge-purge subtype and bulimia nervosa.

“Although we understand a lot about binge eating, many aspects remain puzzling,” said Hildebrandt, research instructor in the Department of Psychiatry at Pitt. “Factors that lead to a re-emergence of binge eating remain unknown, so our goal was to find out if something in the brain may be contributing to the persistence of the behavior.”

Dr. Britny Hildebrandt

To begin to answer these questions, researchers turned to mice.

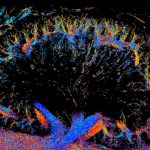

After directly examining neural activity in mice during binge-like eating, Hildebrandt and her colleagues at Pitt found that, unlike mice that had continuous access to palatable food, mice with intermittent binge-like access to palatable food had reduced activity in an area of the brain associated with habit at the onset of eating. These results also suggest that chronic binge eating may share neural mechanisms underlying other psychiatric conditions with repetitive behaviors, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“Unlike previous studies in humans, in our study we are able to use approaches that allow us to directly monitor neural activity — down to the second — during a binge-like eating episode,” said Hildebrandt, who also works as a clinical psychologist in the Services for Kids and Youth with Eating Disorders program through the UPMC Western Behavioral Health Center for Eating Disorders (CED). “These methods give us the opportunity to understand what is happening in this part of the brain during binge-like eating, something that was unknown prior.”

Another program within the UPMC CED, the Help for Overcoming Problem Eating Group, uses weekly outpatient group therapy sessions to help patients address their binge eating behaviors. By providing cognitive behavioral therapy, an evidence-based intervention for binge eating, and incorporating elements of dialectical behavioral therapy, which has shown promise for treating binge eating, the program aims to help patients better understand what puts them at risk for binge eating and to develop healthy alternatives and coping strategies.

“We find that there are a lot of stigmas related to disorders that involve binge eating,” said Dr. Rachel Kolko Conlon, research assistant professor of psychiatry at Pitt who studies eating- and weight-related disorders and provides supervision in the UPMC CED. “Societal weight bias places a focus on a specific body size, weight and shape. For all people, including those who are more vulnerable to binge eating — due to biological, environmental and emotional factors — living in a world that discriminates against being at a higher weight is problematic.”

Sophia Russell is one of many who found herself relapsing after going through treatment for binge eating.

“I went through intensive outpatient treatment for my eating disorder, and afterwards I thought I had my binge eating behaviors under control,” said Russell. “I eventually found myself relapsing, and I knew that there was something in my brain not functioning correctly. This research at the cellular level could be groundbreaking, especially if new treatment options were to be created as a result.”

Erika Ramsey experienced first-hand many stigmas that oftentimes come with binge eating.

“At first, I didn’t even realize that I was suffering from an eating disorder,” said Ramsey. “My binge eating behaviors were tied up with judgment and shame from others about my eating habits. Until I sought out treatment as an adult and started to live in a supportive environment, my eating behaviors were never looked at from a clinical perspective.” Russell and Ramsey are both now in recovery and peer specialists at UPMC.

Dr. Rachel Kolko Conlon

Because Hildebrandt and Conlon are both involved in clinical activities at the UPMC CED in addition to conducting research, they are on the forefront of treating patients and use their clinical experiences to inform new research projects.

Hildebrandt plans to continue her research to understand if correcting abnormal activity in the brains of mice with chronic binge-like eating could lead to a reduction in the behavior to gain even more insight into the brain processes that underlie these behaviors.

“At the end of the day, our goal is to work toward better treatment outcomes for individuals suffering from chronic binge eating, whether that means developing new treatments targeting neural mechanisms or enhancing currently available treatments by incorporating training of new skills in therapy,” said Hildebrandt.

“Our knowledge of binge eating is growing with every study that comes out,” said Conlon. “Research has taught clinicians the importance of assessing binge eating across all populations, as the behavior does not only occur in people with higher body weight or with binge eating disorder.”

Journalists interested in learning more can contact mediarelations@upmc.edu.