Those unlucky enough to be infected by the mosquito-borne chikungunya virus (CHIKV) often find themselves debilitated for months or even years by painful joint and muscle inflammation.

Development of effective treatments and vaccines for CHIKV has been complicated by the virus’s capacity to infect a wide variety of cells and tissues. Without a precise idea of which cells and tissues support CHIKV infection, virologists have been left without a clear understanding of how the virus causes its characteristically painful symptoms.

But researchers in the laboratory of Dr. Terence S. Dermody at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine recently identified a key facet of how CHIKV causes disease in mice – and took steps to identify both a vaccine candidate and a treatment for the virus.

But researchers in the laboratory of Dr. Terence S. Dermody at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine recently identified a key facet of how CHIKV causes disease in mice – and took steps to identify both a vaccine candidate and a treatment for the virus.

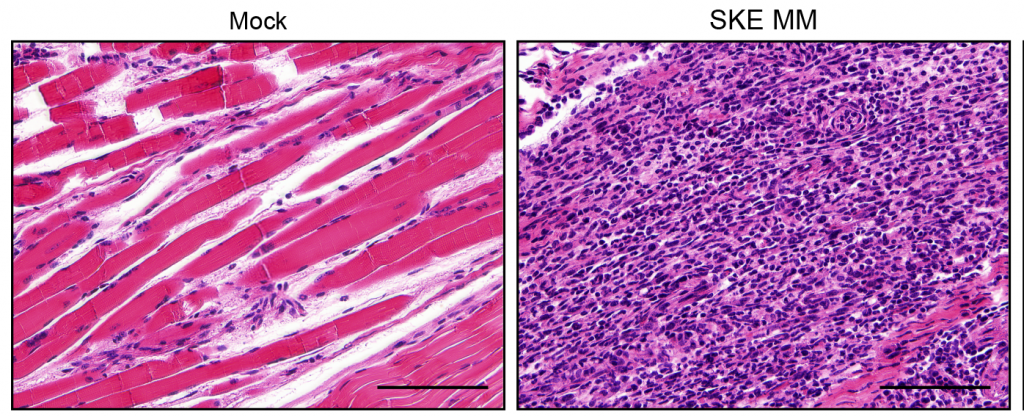

According to their study in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, reduction of CHIKV replication in mouse skeletal muscle cells potently lessened the painful tissue inflammation seen during chikungunya disease. But what surprised the researchers was that restricting replication within skeletal muscle cells did not significantly reduce the amount of virus found residing within surrounding tissues or within the mouse itself.

“We usually think that the more virus you have at a site, the more disease it’s going to cause,” said lead author Anthony Lentscher, a graduate student within Pitt’s Program in Microbiology and Immunology. “But our study shows that this isn’t true for all viruses. The quantity of virus and disease are not always coupled.”

The group “barcoded” their virus by attaching a genetic sequence that is recognized and suppressed by miR206, a molecule that is specifically expressed in skeletal muscle cells. This restricted the barcoded virus from spreading within skeletal muscle tissue and allowed the investigators to examine the role that viral replication in these cells plays in chikungunya disease. Dr. Dermody, who is also physician-in-chief and scientific director at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, noted that “the technical innovation of the barcoded virus enabled this study to be done.”

The barcoded virus caused significantly weaker disease symptoms, but could still functionally replicate within infected mice and activate the body’s immune response – a fundamental feature of pathogens used in live-attenuated vaccines.

“We like the idea of a live-attenuated virus because it replicates in tissues CHIKV would normally infect and initiates a durable and robust protective immune response,” said Lentscher.

Comparison of skeletal muscle inflammation in uninfected (left) and CHIKV-infected tissue (right). Infection with CHIKV causes severe infiltration of inflammatory white blood cells (purple spots), which is reduced in the miR-206 restricted virus.

Lentscher stressed that this attenuated or weakened version of CHIKV probably will not be a vaccine candidate by itself, and the research team is looking to combine the barcode in this virus with other mutations previously shown to attenuate the virus.

“It’s like a vaccine toolbox,” said Lentscher. “We’re taking a bunch of different attenuating mutations to make the safest and most immunogenic vaccine candidate possible.”

In addition to this study’s contributions towards a CHIKV vaccine, the research team also may have identified a potential treatment for individuals suffering from CHIKV-induced joint and muscle pain.

The group treated CHIKV-infected mice with an antibody that inhibits an inflammatory cascade triggered by a protein called the IL-6 receptor, and observed a significant decrease in muscle swelling and inflammation.

Lentscher said that an IL-6 receptor inhibitor, called Tocilizumab, has been licensed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and could be adapted to treat the symptoms of CHIKV infection.

“I think that repurposing Tocilizumab would be helpful, especially because we see these massive epidemics breaking out in populations that previously hadn’t had widespread chikungunya,” he said. “There are a lot of people suffering from acute CHIKV disease.”

Ryan Staudt is a molecular pharmacology Ph.D. candidate in the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. He is participating in a UPMC Science Writing Mentorship Program.