For up to 3 million Americans each year, what was supposed to be a fun day at the ski slopes, at a playground or on a football field quickly takes a turn for the worse. While simple steps – such as wearing a helmet – can prevent serious head injury resulting from a sudden high-impact fall or a blow to the head, those measures are less effective at preventing concussions.

In collaboration with the UPMC Concussion group, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh Department of Ophthalmology discovered that recording and analyzing patterns of fixational saccades – tiny involuntary eye movements that help maintain the gaze on a stationary object or location – can be used to develop fast, non-invasive and reliable tools to identify vision impairment following concussion, which sometimes goes undiagnosed. The report was published recently in the Journal of Vision.

“Our group was the first to precisely evaluate fixational eye movements in patients following a concussion,” said senior author Dr. Ethan Rossi, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Pitt.

Concussion is a mild traumatic brain injury. People suffering from a concussion often feel dizzy, experience headaches and can develop vision problems. Identifying all symptoms and impairments requires a careful and comprehensive assessment – and the success of a patient’s recovery hinges on it.

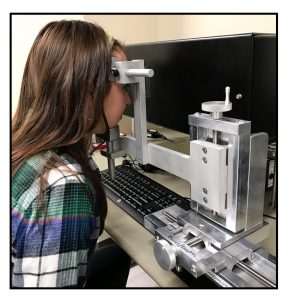

First author Bianca Leonard using the system that allows tracking small involuntary eye movements. Credit: Ethan Rossi, Ph.D.

Although there is no single treatment for all concussions, treatments that target anxiety and headache, and that are aimed to restore brain function, balance and vision, can accelerate recovery. Still, the tools for evaluating vision impairments following concussions are limited, which can lead to missed opportunities for more effective treatments.

To address that issue, the researchers tested whether concussion affects small involuntary eye movements, and whether that measurement can be used to assess vision impairments in patients. The scientists found that young adults and adolescents who were tested several days after their concussion had greater fixational saccade amplitude – meaning that their involuntary eye movements were larger and less precisely controlled than normal — when trying to focus on the center of an object than those without concussion. The finding points at the possibility of using that parameter, and potentially other metrics based on eye movements, to reliably assess visual dysfunction in people with suspected concussion.

And the technology to measure the saccades already exists. The researchers collaborated with a biotechnology startup from Boston, led by vision science expert Dr. Christy Sheehy, that developed and patented an eye-tracking device that’s capable of recording and analyzing eye movements with higher precision than existing commercial devices.

“This technology has the potential to add objectivity to our ability to identify visual impairment in patients following concussion that might otherwise go undetected using current clinical evaluations,” said co-author Dr. Anthony Kontos, director of the UPMC Sports Medicine Concussion Program. “Using eye movement analysis can complement current clinical assessments and provide a more objective, measurable outcome to identify and track patients’ recovery.”