Scientific research rarely follows a straight line. And Dr. Brian Campfield’s latest study, recently published online and scheduled for an upcoming print issue of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, is a prime illustration of pursuing the scientific journey where the data lead.

As a pediatric infectious disease fellow, Campfield was studying the immune effects of a protein that contributes to Lyme arthritis – and it led him to an investigation of that same protein in emphysema, a condition far more commonly found in adults with a history of smoking than in children.

As a pediatric infectious disease fellow, Campfield was studying the immune effects of a protein that contributes to Lyme arthritis – and it led him to an investigation of that same protein in emphysema, a condition far more commonly found in adults with a history of smoking than in children.

Campfield, M.D., assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, answers questions about the latest steps in his research.

Inside Life Changing Medicine: Tell us about emphysema – what do we already know about how people get it and what is still a mystery?

Brian Campfield: Emphysema is a complex, chronic lung disease that is one of the manifestations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, or COPD. The most common cause is smoke exposure, typically from cigarettes. However, smoke doesn’t explain it all; sometimes non-smokers develop emphysema. Genetics plays an important part, but the medical-scientific community has only been able to identify a handful of genes that are associated with COPD or emphysema despite spending a great deal of effort.

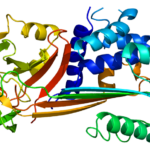

ILCM: Your research centers on follistatin-like protein-1 (FSTL-1). What is it and why is it important?

BC: FSTL-1 is not very well understood, but it’s important in protecting the lung from disease. We found that it’s made in the lung by connective tissue, blood vessel and air exchanging cells, where it acts on immune cells to keep the immune system from getting started inappropriately.

ILCM: Please explain how you designed your study.

BC: We collaborated with research groups here at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and across the University of Pittsburgh, and we also worked with experts on lung disease, COPD and FSTL-1 biology across the country. We examined the lungs of FSTL-1 deficient mice like a physician would examine a patient suspected of having COPD: lung function tests, CT scans, biopsies. Then we looked to see exactly what cells make FSTL-1 and what genes it regulated. Finally, we looked at whether people with COPD had mutations in the FSTL1 gene itself.

ILCM: What did you discover?

BC: In our study, we found that FSTL-1 deficient animals developed emphysema even without smoke-exposure, confirming that mutation of the FSTL1 gene alone was enough to cause emphysema. We also found that FSTL-1 regulates an immune master control gene, called Nr4a1, a connection that was previously unknown. In humans, we found that FSTL-1 mutations are not very common in people, but when they occur they often are associated with COPD.

ILCM: Did any of your findings surprise you?

BC: Frankly, most of them. We were very surprised to observe that cigarette smoke doesn’t make emphysema worse. We need to do more studies into how FSTL-1 deficiency appeared to protect against cigarette smoke damage. But this is the nature of scientific discovery.

ILCM: Can this be translated to human treatment?

BC: These findings are suggestive that some cases of human COPD may be due to abnormal FSTL-1 function, but we need to do more work to know how common FSTL-1 driven lung disease is. We also need to know how we can enhance or block FSTL-1 in certain diseases. There’s a lot to figure out.

ILCM: What are the next steps?

BC: We need to get back in the lab and really understand the fundamental biology of FSTL-1. But we also need to get in the clinic and the hospital to identify patients with diseases caused by abnormalities in FSTL-1, specifically patients with COPD and other lung diseases.