Scientists at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine have discovered a tuberculosis (TB) vaccination strategy that could prevent the leading cause of death among people worldwide living with HIV.

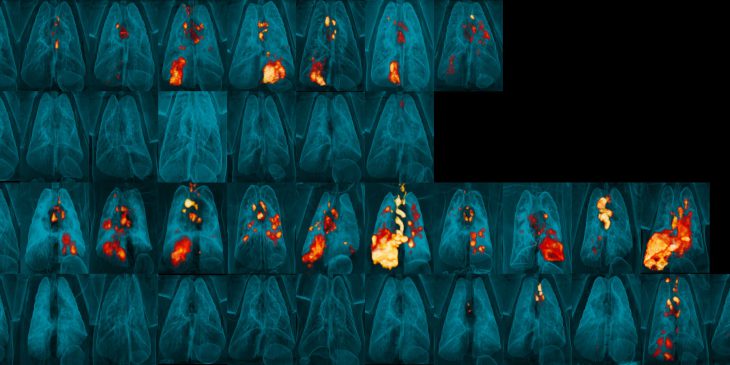

The results, published this week in Nature Microbiology, showed that, when given intravenously, the only commercially available vaccine against TB successfully and safely prevents lung infection in monkeys infected with the simian, or primate, form of HIV, called SIV. This is despite the vaccine being contraindicated for people living with HIV.

“What is really exciting about this study is that, for the first time, we’re seeing complete protection from TB in a model of HIV. This hasn’t been shown before,” said lead author Dr. Erica Larson, research assistant professor in Pitt’s Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. “This shows that there’s potential to protect people living with HIV against TB.”

Dr. Erica Larson

One in three people living with HIV die of TB, which is caused by a bacterium called M. tuberculosis that usually attacks the lungs. It is the world’s second-leading infectious killer after COVID-19. About 1.6 million people die of TB annually, including almost 200,000 people living with HIV, according to the World Health Organization.

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is a vaccine against TB that has been around for 100 years and is among the most widely used vaccines in the world. It is made of a live, but weakened, form of M. bovis, a bacteria closely related to M. tuberculosis. BCG is mostly given to infants and children via injection into the skin, but it offers minimal protection from M. tuberculosis, particularly against infection of the lungs.

In a landmark study published in Nature in 2020, a team of scientists at Pitt and National Institutes of Health showed that when monkeys are given the BCG vaccine intravenously — injected directly into a vein — it is highly protective against TB, including lung infections.

The new study builds on these findings.

“We almost didn’t do this study with this vaccine out of fear that the vaccine itself would cause serious disease in these immunocompromised animals,” said senior author Dr. Charles Scanga, research associate professor in Pitt’s Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. “BCG is a live bacteria. It is safe for people with healthy immune systems, but HIV suppresses immunity, and even weakened bacteria can be fatal.”

Dr. Charles Scanga

With the encouraging results from the previous Nature paper, the team decided to go forward with the experiment. But they did something unique. About three weeks after vaccination, they gave the monkeys antibiotics to kill all the live attenuated bacteria in the vaccine. Their hope was that the BCG had enough time to stimulate the immune system to protect against a real TB infection, but not enough time for the weakened bacteria in the vaccine to cause disease in the immunocompromised monkeys.

The gamble paid off. Not only did none of the animals get sick from the BCG vaccine but, most importantly, 75% of the monkeys with SIV that were vaccinated intravenously and then given antibiotics a few weeks later went on to successfully fight off TB infections. Intravenous BCG vaccination also protected all the monkeys without an SIV infection. The only animals in which the vaccine did not work to prevent TB were those that had the worst SIV disease, likely because the SIV had already wiped out the immune cells, meaning there were none left for the vaccine to train to fight TB.

The scientists note that it isn’t going to be practical — especially in low- and middle-income countries — to give this vaccine intravenously to people with HIV and then expect them to come back in a few weeks to take antibiotics to prevent the BCG vaccine from causing disease. They plan to test the safety of intravenous BCG without using any antibiotics, as well as testing new BCG vaccines in development that self-destruct before that can cause disease in immunocompromised people, yet are still able to prevent TB.

“TB is rampant in parts of the world where there isn’t a really good public health infrastructure,” said Scanga, who is also a member of Pitt’s Center for Vaccine Research. “Unfortunately, those are also places where HIV goes undiagnosed or untreated and spreads. So, epidemiologically, TB and HIV go hand-in-hand. Prevention in the form of a realistic TB vaccination strategy is going to be key to saving hundreds of thousands of lives each year. And I’m hopeful that our study is a big step in that direction.”

Journalists interested in learning more can contact mediarelations@upmc.edu.