The pastel colors of the evening sky, the bright plumage of a rare bird, a delicate flower growing through the concrete – we experience the world through our eyes, and yet the eye is a microcosm in and of itself. Supplied with more nerves than any other organ in the body, the eyes remain a source of mystery for scientists studying health and disease.

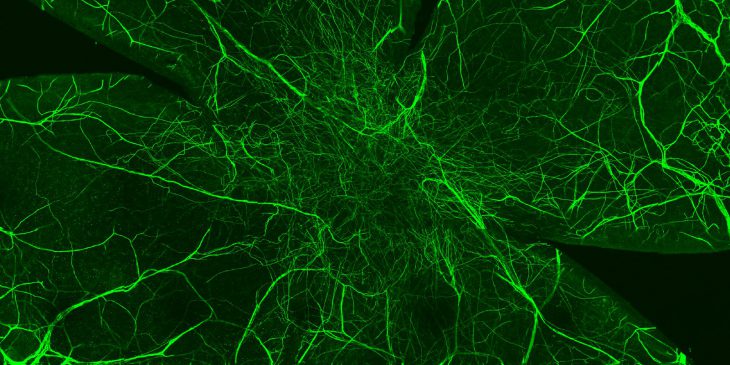

An FDA-approved VEGF-A-neutralizing treatment can reverse the loss of sensory nerves in herpes virus-infected corneas in mice. Credit: Anthony St. Leger, Ph.D.

In a paper published recently in the journal Immunity, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh Department of Ophthalmology uncovered a mechanism by which herpes virus hijacks the precarious relationship by which the nervous and immune systems maintain a balance between different types of nerves that supply electrical signals to and from the eye.

“In the past, people who studied corneal disease focused on either a neural or immune component, rarely experimenting with how the two communicate,” said lead author Dr. Hongmin Yun, a research assistant professor of ophthalmology at Pitt. “Now we know that we have to consider both sides to capture all aspects of the disease.”

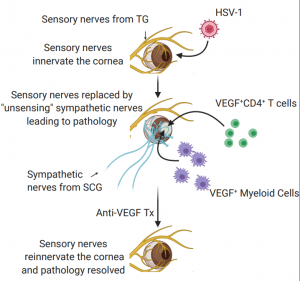

The herpes virus, researchers found, forces sensory nerves that sense stimuli and control our blink reflex to retract. These nerves are replaced by sympathetic nerves which, by design, do not carry any sensations. This mechanism, scientists say, is responsible for the loss of vision that is often associated with advanced stromal keratitis – a condition where the cornea develops a lesion that disrupts the ability of light to enter the eye. In this study, the disease was caused by the herpes virus; however, stromal keratitis can be caused by other viruses, bacteria or fungi.

Until recently, corneal transplant was among the few options available to treat advanced keratitis and vision loss. The new study, however, gives reasons to be optimistic about less invasive treatments.

Researchers found a culprit that disrupts sensory innervation in the eye after the infection – a chemical factor produced by immune cells infiltrating the injured eye, called vascular endothelial growth factor A, or VEGF-A. And, fortunately, the cure might be within reach.

Scientists showed that a Food and Drug Administration-approved VEGF-A-neutralizing treatment widely used as a treatment for cancer, age-related macular degeneration and other diseases can reverse the loss of sensory nerves in herpes virus-infected corneas in mice.

“We found that immune cells that produce VEGF-A get recruited to fight the pathogen but cause collateral damage along the way,” said senior author Dr. Anthony St. Leger, assistant professor of ophthalmology and immunology at Pitt. “But we might have a promising therapy right in front of us.”

Researchers still have a long way to go. They are developing a mouse model that better approximates the way corneal herpes virus infection progresses in humans and working out what causes immune cells to ramp up VEGF-A production.

Still, Yun and St. Leger’s work holds promise.

“It is very exciting to see how a completely opaque cornea, one where you can’t even detect the iris, can become transparent again,” said Yun. “Now, in serious cases of keratitis, there might be another option to regenerate sensory nerves and restore vision.”