A human adult is made up of trillions of cells invisible to the human eye. And despite modern technology stripping away layers of mystery, our bodies still hide much information from scientists. How cells interact, connect and arrange into tissues and organs has a direct effect on our health.

“Our current ways of overall mapping the human body are limited,” said Dr. Jonathan Silverstein, a visiting professor in the Department of Biomedical Informatics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “There’s not enough data right now to address different diseases.”

Silverstein is part of an international cohort of medical scientists that’s creating a new, interactive 3-D map of the human body down to the cellular level, which is being called “Google Maps for the body.”

HuBMAP patches together blood samples to create the 3-D human body map.

The Human BioMolecular Atlas Program — or HuBMAP for short — aims to be an atlas of sorts for medical doctors by helping them understand relationships between cell and tissue organization and function, as well as human health. HuBMAP this week released its first batch of data for use by the scientific community and the general public, which can be found at portal.hubmapconsortium.org.

Pitt is working with Carnegie Mellon University and the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, a joint institute of the two universities, to build software that makes the collected data useable.

“This will create a tremendous amount of information about how normal cells operate,” said Silverstein, who is also chief research informatics officer for health sciences and Pitt’s Institute for Precision Medicine. “Comparing normal cells to different disease conditions will be very informative for developing strategies to treat a variety of diseases.”

HuBMAP consists of 18 diverse collaborative research teams across the United States and Europe, and is managed by a trans-National Institutes of Health working group of staff from the NIH Common Fund; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

“If we’re learning one thing this year, it’s that we must embrace our technology, creativity and commitment to collaboration to leverage our research advances,” said Dr. Rob A. Rutenbar, Pitt’s senior vice chancellor for research. “In many ways, the goal of HuBMAP isn’t just to develop an open and global platform to map healthy cells; it’s to build and use this collective knowledge base as rapidly and effectively as possible.”

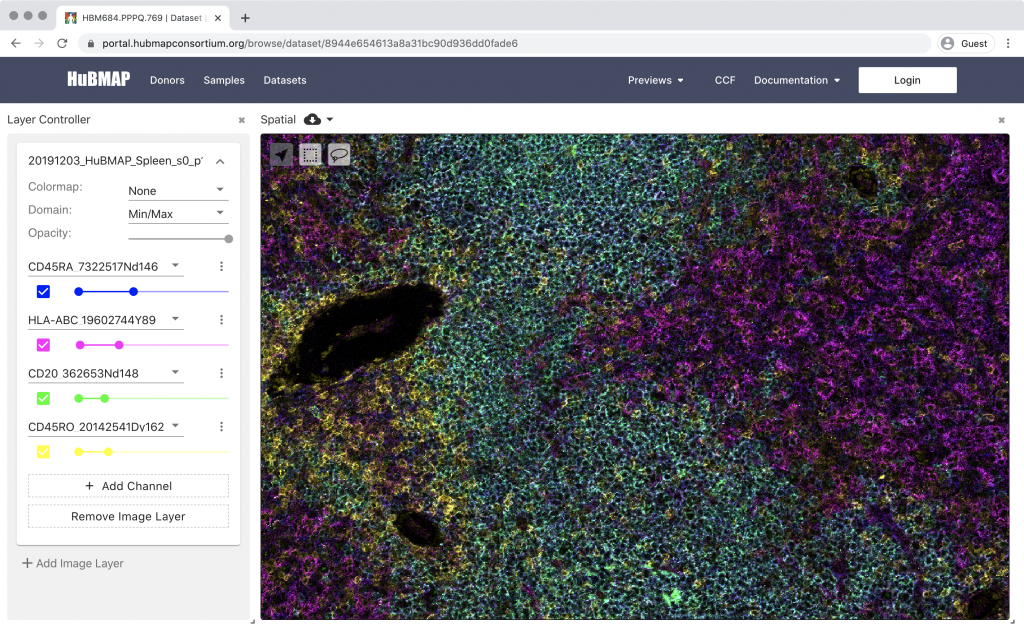

The project takes blood samples from different parts of the body from donors. The samples are then patched together to create the 3-D human body map. People can explore the map to see what cells look like for body parts such as the spleen, heart and intestines among others. For example, doctors can use HuBMAP to understand how differences between individual cells in the body lead to normal development or progression of disease. They can also use it to visualize tissues to explain diseases and treatments to patients. Educators can also use the map to teach students about the human body and how cells function.

“I’ve done a lot of big projects in my career, but this is without a doubt the most exciting one, because the number of ways this is going to be used is just extraordinary,” said Silverstein. “It will be a large, national resource for a long time.”