New research from the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy sheds light on the processes that lead to liver fibrosis and suggests a novel treatment approach for this common and serious condition.

Led by senior author Dr. Wen Xie, professor and Joseph Koslow endowed chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and co-first authors Hung-Chun Tung, graduate student, and Dr. Jong-Won Kim, postdoctoral fellow, the study published today in Science Translational Medicine.

Dr. Wen Xie

In this Q&A, Xie elaborates on the study’s findings and explains why new diagnostic tools and treatment options for liver fibrosis are greatly needed.

What is liver fibrosis and who is at risk?

Liver fibrosis is the formation of tissue scars in the liver due to chronic inflammation and injury. Over time, fibrosis can impair liver function and may lead to cirrhosis or even liver cancer. Those at risk include individuals with chronic viral hepatitis, obesity, diabetes and excessive alcohol use. Early detection and intervention are crucial to prevent progression to more severe liver disease.

What are the current treatments for liver fibrosis?

Currently there are no FDA-approved drugs that specifically treat liver fibrosis. The only treatment option is to treat diseases that cause liver fibrosis in the first place, such as hepatitis, obesity, type 2 diabetes and alcoholic liver disease. Preventive measures include avoiding excessive alcohol, maintaining a healthy body weight and early screening for liver diseases to prevent fibrosis from advancing to cirrhosis or liver failure.

What are hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), and how do they contribute to liver fibrosis?

HSCs are a unique cell type in the liver. When the liver is injured or inflamed, HSCs become activated and produce excess collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins. The accumulation of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins leads to scar tissue formation and liver fibrosis.

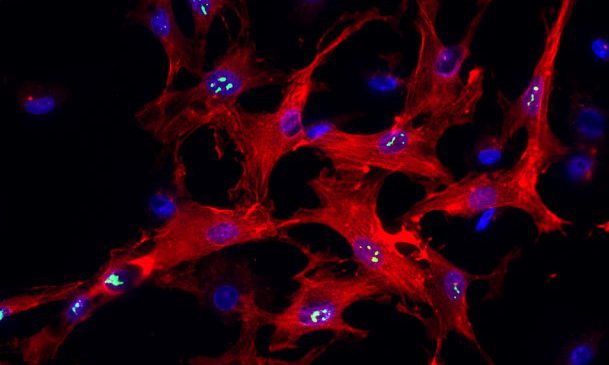

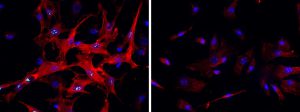

Microscopy image showing activated HSCs, indicated by red staining (left image). Inhibition of CYB1B1 reduces HSC activation (right image), which leads to reduced liver fibrosis (CREDIT: Tung et al., Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadk8446 (2024)).

What were the main findings of this study?

This study identified the enzyme CYP1B1 as a biomarker and predictor of HSC activation and liver fibrosis in both patients and mice. Inhibition of CYP1B1 led to the accumulation of a sugar called trehalose, which we showed for the first time that trehalose has anti-fibrotic activity. Moreover, treatment of mice with trehalose, its analog lactotrehalose or CYP1B1 inhibitor protected mice from getting liver fibrosis.

It was surprising to identify a liver function of CYP1B1, an enzyme traditionally known for its functions outside the liver. Although the concentration of CYP1B1 in the whole liver is not high, this enzyme is uniquely and abundantly present in HSCs and thus plays an important role in HSC activation and liver fibrosis.

What are the clinical implications of these findings?

Liver fibrosis is a common, potentially deadly and costly liver disease that lacks FDA-approved drugs. Our findings are clinically important because we identified CYP1B1 as a predictor of HSC and liver fibrosis in patients, which may help with the early diagnosis of this disease. More importantly, we found that trehalose and lactotrehalose are potential novel drugs that could be used to treat liver fibrosis in the future.

What’s next for this research?

Future and more comprehensive human studies are needed to confirm the role of CYP1B1 in human liver fibrosis. The utility of trehalose or lactotrehalose in the treatment of human liver fibrosis also warrants future studies.