Is it a droplet? Or an aerosol? When it comes to the spread of respiratory viruses, the answer matters – even if it means challenging conventional wisdom.

In a recent article in the journal Science, an international team of scientists that included University of Pittsburgh virologist Dr. Seema Lakdawala called for an update to the traditional view of how we transmit many common diseases. Breathing in virus-laden aerosols, not only large droplets, is how respiratory viruses pass from person-to-person, the team concluded.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has changed many aspects of our lives – including how we think about viruses and the ways they spread,” said Lakdawala, assistant professor in Pitt’s School of Medicine and member of Pitt’s Center for Vaccine Research. “What we’re learning from SARS-CoV-2 – the virus that causes COVID-19 – is sharpening our knowledge of many other respiratory diseases, including flu, common cold-causing viruses and measles.”

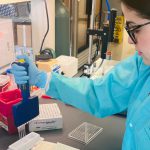

Dr. Seema Lakdawala in her lab

Over the last century and at the beginning of this pandemic, clinicians and public health officials widely believed that respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, mainly spread through droplets produced by the coughs and sneezes of infected people or through touching surfaces contaminated with fomites, which are droplets containing infectious virus particles that settle on objects and surfaces.

However, droplet and fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 fails to account for the numerous superspreading events involving asymptomatic people that have been observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, or the much higher odds of transmission when indoors.

Lakdawala and the research team – which includes chemists, pulmonologists, engineers, sociologists and microbiologists from Taiwan, the U.S. and Israel – took a deep dive into existing research and investigations to identify as clearly as possible how the coronavirus and other respiratory viruses move from person to person.

The evidence and studies laid bare that these viruses are spread by people breathing in virus-laden aerosols at both short and long ranges. Droplets from sneezes or coughs hitting others in the mouth or nose, or people carrying the virus from a doorknob to their face are not the only way in which these viruses can spread.

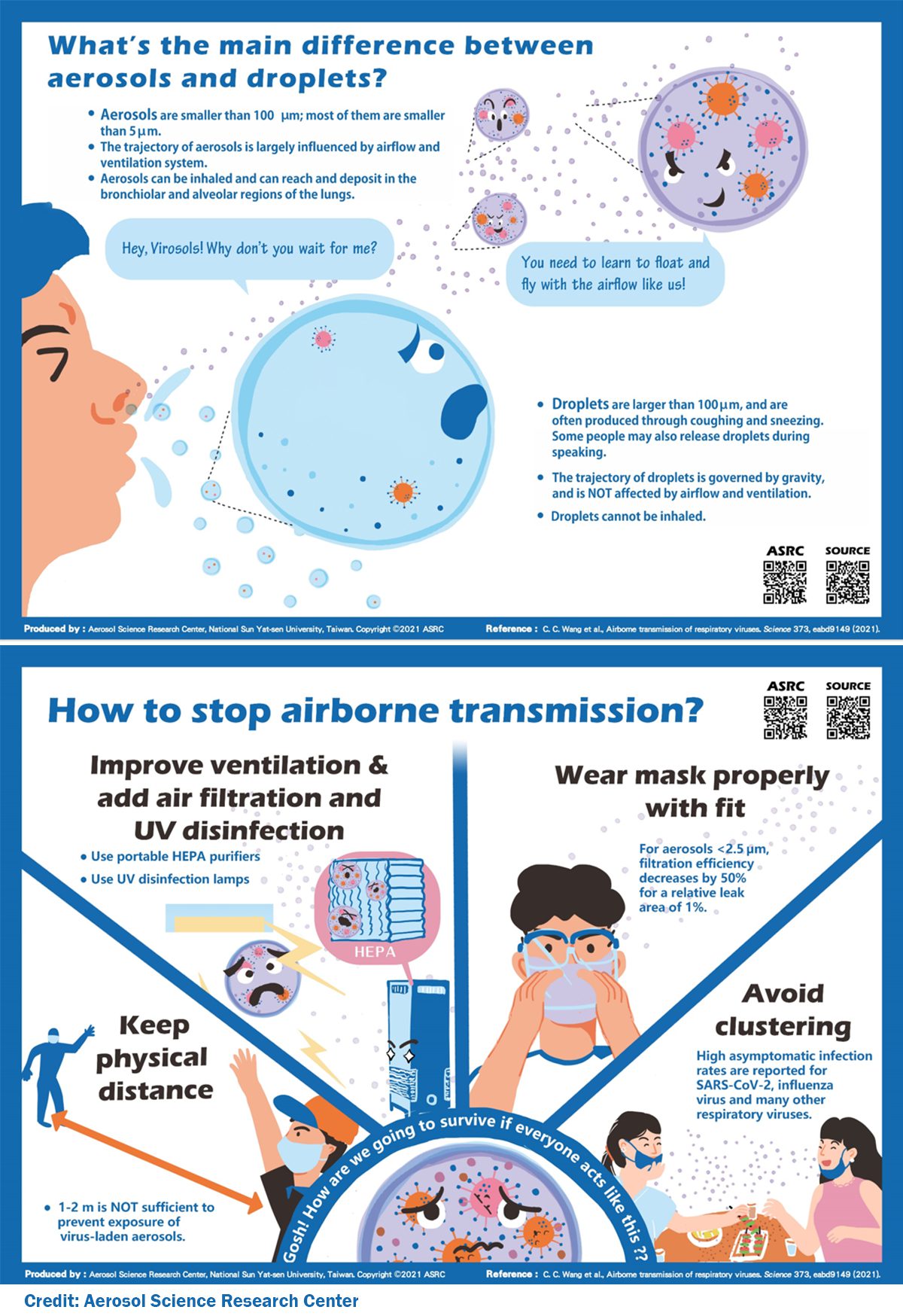

Respiratory aerosols are formed when people breath, talk, sing, shout, cough or sneeze. Before COVID-19, the traditional size cut-off between aerosols (which float in the air) and droplets (which drop) was 5 microns, a size invisible to the eye. Now the scientists say that definition should be changed to 100 microns, the width of an average human hair – still very small, but visible – and able to stay suspended in still air for more than 5 seconds, long enough to float beyond three feet from an infected person and be inhaled.

A 100-micron respiratory aerosol could carry hundreds of SARS-CoV-2 viruses.

Knowing how respiratory viruses spread has a significant impact on efforts to stymy that spread, Lakdawala said. For example, sufficient ventilation rates, high-quality air filters and UV disinfection in ventilation systems, as well as avoiding recirculation of unfiltered air, can reduce the concentration of virus-laden aerosols, while plexiglass barriers could actually impede proper ventilation and create higher exposure risks.

The team noted that it is important to help all people understand that respiratory viruses spread by aerosols as well as droplets so they can visualize the ways they can help strop transmission. For example, masking is an economic way to block respiratory aerosols but isn’t enough on its own.

“We need to consider multiple barriers to transmission, such as vaccination, masking and ventilation,” Lakdawala said. “One single strategy is unlikely to be strong enough to eliminate transmission of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants that hitch a ride on respiratory aerosols.”